This past week in Busan, South Korea, negotiators from 175 nations convened for the fifth and final planned meeting of the U.N. Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC-5) to address the global crisis of plastic pollution. Despite the urgency of the issue, the talks ended without a consensus, delaying any progress until negotiations resume next year. At the heart of the impasse is whether the treaty should include measures to reduce overall plastic production and impose global, legally binding controls on the toxic chemicals used in plastics.

Google ai-gen conversation about this topic:

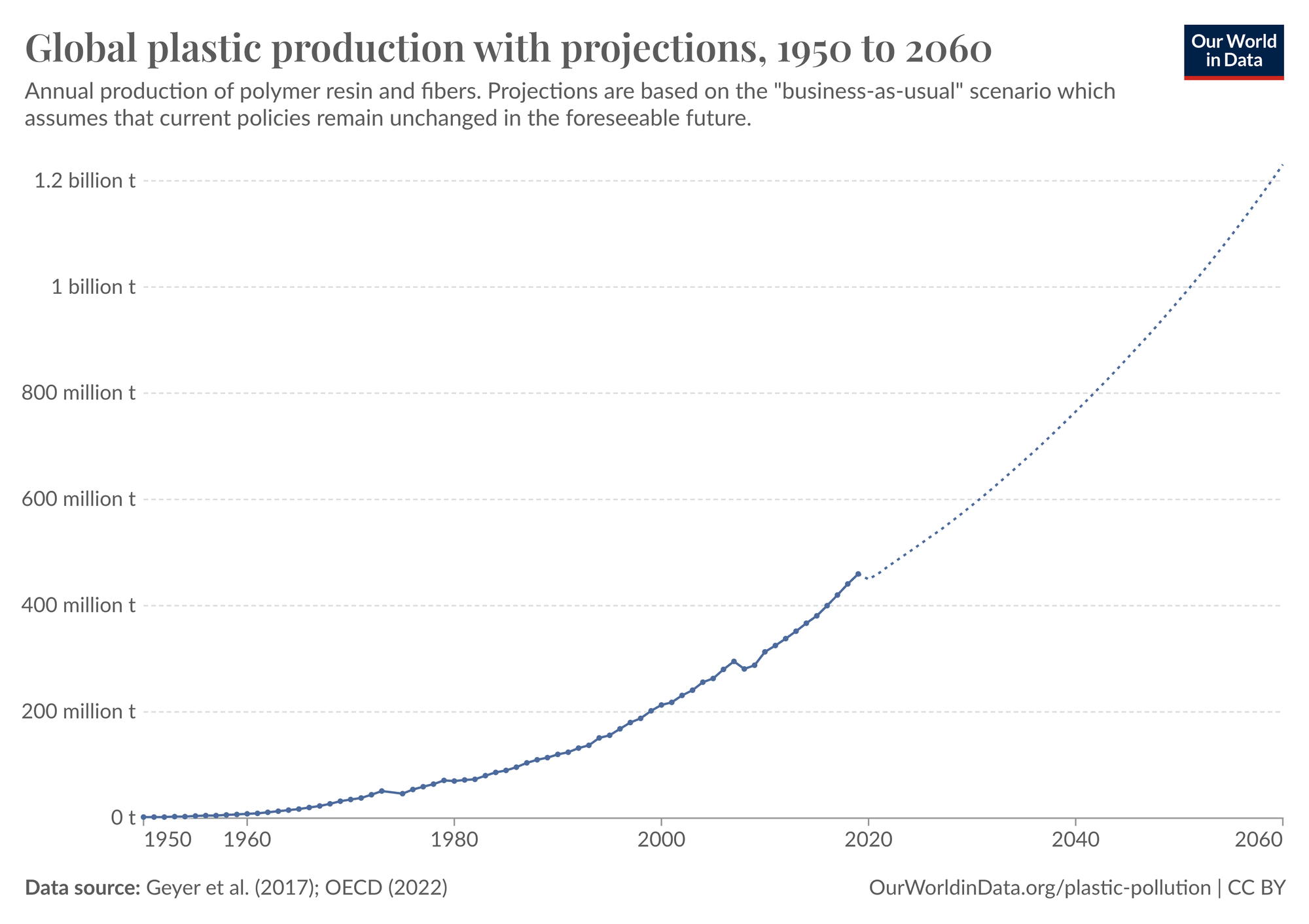

Plastic pollution represents a critical threat to the environment, public health, and global economies. In 2024, humanity is expected to consume over 500 million tons of plastic, with more than 90% discarded as waste shortly after use. By 2040, production is projected to surge by 70%, reaching 736 million tons annually. While production itself is not inherently the issue, the mishandling and accumulation of discarded plastic waste are causing widespread and dangerous impacts on ecosystems worldwide.

Estimates of plastic entering the oceans vary, with UNEP reporting 13 million tons annually and Oceana USA suggesting up to 33 million tons. This growing influx has alarming consequences: a BSAC survey revealed that 60% of fish examined contained microplastics in their flesh. Further research highlights that microplastics absorb toxic chemicals, compounding the contamination of the food chain. Without significant intervention, plastic pollution entering aquatic ecosystems is expected to nearly triple by 2040, exacerbating an already dire environmental crisis.

Microplastics are not just confined to the oceans; they permeate the air and food supply. A 2023 literature review by Yale Environment highlighted airborne microplastic concentrations ranging from 0.01 particles per cubic meter in the Pacific Ocean to thousands per cubic meter in urban centers. Atmospheric chemist Zamin Janji suggests these figures are likely underestimated. A 2024 World Economic Forum report further confirmed microplastics are ubiquitous in the global food supply.

The negotiations aimed to create the first legally binding treaty on plastic pollution, but progress was stymied by fundamental disagreements. Key producing nations, including Saudi Arabia, India, Kuwait, and Iran, opposed efforts to limit production or regulate the toxic chemicals in plastics. Saudi Arabia’s negotiator, representing the Arab group, argued that the treaty’s focus should be on managing pollution rather than reducing plastic production itself. Kuwait’s negotiator echoed this sentiment, stating that eliminating plastic pollution does not necessitate ending plastic production.

The process for creating the treaty began in March 2022 when 175 nations agreed to work toward a legally binding agreement to address plastic pollution, including marine debris. However, in Busan, negotiators failed to bridge divides on the critical issues - chemicals of concern, plastic production, financing mechanisms, and treaty principles. Luis Vayas Valdivieso, the committee chair from Ecuador, acknowledged that while some progress had been made, significant gaps remain.

Environmental groups and other stakeholders criticized the closed-door nature of the negotiations and the lack of representation from impacted communities, scientists, and health experts. Bjorn Beeler, international coordinator for the International Pollutants Elimination Network, stated, “The voices of the impacted communities, science, and health leaders are silent in the process, and to a large degree, this is why the negotiation process is failing. Busan proved that the process is broken and just hobbling along.”

As plastic pollution continues to accumulate at alarming rates, the failure to reach a meaningful agreement highlights the difficulty of balancing environmental priorities with economic and geopolitical interests. Without significant progress, the environmental, social, and health costs of plastic pollution will only escalate.