During the November 22 conclusion of COP29, the world’s wealthiest nations announced a pledge of $300 billion annually by 2035 to assist developing countries in addressing the impacts of climate change. Leaders from the Global North hailed the agreement as a historic milestone, with claims of unprecedented ambition. However, developing nations quickly dismissed the pledge as “woefully inadequate,” with some labeling it a bad joke, given that the estimated financial needs to confront climate change are closer to $1.3 trillion annually. This disparity raises a pressing question: is this pledge a genuine step forward, or merely another hollow gesture in the theater of climate diplomacy?

Who’s Paying What?

The pledge includes contributions from 23 wealthy economies, including the EU, the US, and the UK, aimed at supporting poorer nations in adapting to climate change and transitioning to greener economies. However, no country has yet committed a specific amount, leaving the deal’s execution hanging in the balance.

For some, even the concept of tripling the previous 2009 commitment of $100 billion annually sparks skepticism. Swiss Environment Minister Albert Rösti exemplified this hesitancy, calling the new target “utopian” and stating Switzerland will not allocate additional public funds. Instead, any increase would need to come from private sources, reflecting broader resistance among wealthy nations to significantly bolster public contributions.

US President Joe Biden called the agreement “ambitious,” while EU Climate Commissioner Wopke Hoekstra described it as heralding a “new era in climate finance.” Yet, analysts argue this so-called “new era” looks remarkably similar to business as usual.

Is It Really a Game-Changer?

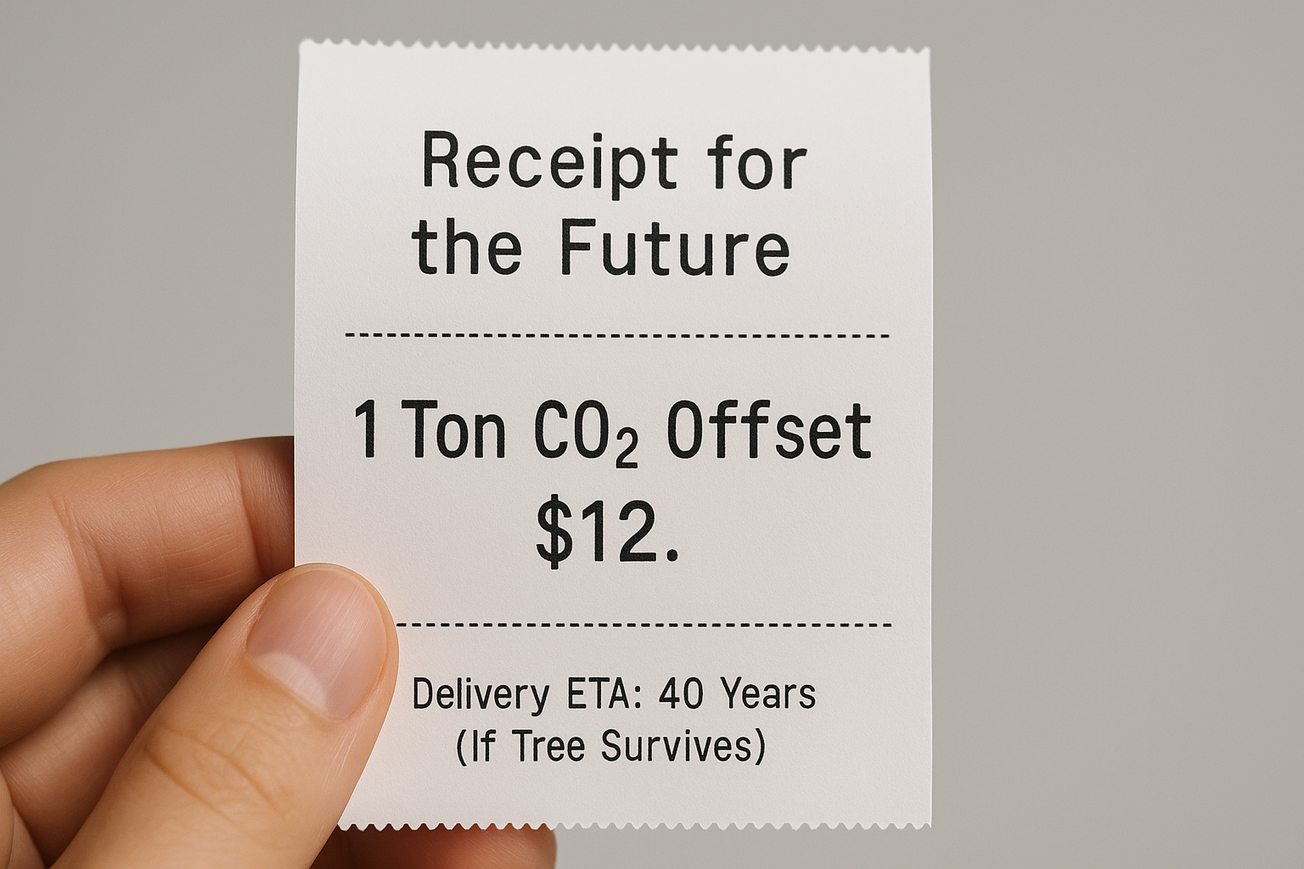

According to the Center for Global Development (CGD), the $300 billion annual target is achievable with minimal effort from the Global North beyond pre-existing commitments. Estimates suggest that by 2030, developed nations would already be on track to provide around $200 billion annually, based on current pledges from governments, multilateral development banks, and private sources. This leaves just $100 billion to bridge—a gap that could theoretically be met without any substantial new financial commitments. Developing nations fear that donor nations will simply redirect or rebrand existing development aid to meet climate finance goals, effectively robbing Peter to pay Paul.

The Real Cost of “Aid”

A 2022 report by CARE Denmark found that much of the public climate finance reported by rich countries between 2011 and 2018 was repurposed from existing development aid budgets. Similarly, the CGD analysis revealed that the 2009 $100 billion target was only met because a third of the funding was redirected from unrelated aid initiatives.

The Broader Implications

The global south’s frustration with the COP29 finance deal underscores a deeper crisis in climate diplomacy: the persistent disconnect between promises made by wealthy nations and the tangible financial support needed by those most vulnerable to climate change. The absence of binding commitments, coupled with the tendency to rebrand existing aid as “climate finance,” undermines trust and exacerbates global inequities.

While leaders in the Global North tout the pledge as a victory, developing nations view it as a hollow gesture—insufficient to address the mounting challenges of rising sea levels, intensifying storms, and climate-induced migration. Without concrete financial commitments and genuine collaboration, the world risks deepening the divide between those who caused the climate crisis and those bearing most of its brunt.

The Verdict

The COP29 climate pledge has been presented as a significant milestone, but its vague commitments and heavy reliance on existing funding cast serious doubt on its potential for real impact. If this represents the dawn of a "new era" in climate finance, it appears to be defined more by lofty rhetoric than the decisive action required to address the escalating climate crisis. As the Global North grapples with its own mounting costs of adapting to a warming world, the pressing question remains: will they shoulder the responsibility to assist the most vulnerable nations, or leave them to face the devastating consequences alone?