To put Earth Day in perspective, it’s important to understand how long the general public has been aware of the need to resolutely address environmental problems, including global warming.

I’ve had the opportunity to work in the environmental movement at local community, national and international levels for more than five decades. It all started when I worked as a regional coordinator of college campuses for the First Earth Day in 1970. On this Earth Day 54 years later, I’d like to share with you what I’ve seen that has worked and where we’re repeatedly failing and perhaps why.

Inspired by Bell Labs

My own interest in environmental issues was first sparked by a popular 1958 science television series by Bell Labs which portrayed a warming earth with melting ice caps, presenting the general public with a clear warning that we needed to address climate change. Although alarming, there were few direct actions available to the interested elementary student I was at the time.

By the late 1950’s, the basic science behind global warming was well established, and by the early 1960’s the environmental damage associated with the post World War II boom had reached a crisis level, with industrial pollution causing rivers to catch fire and creating smog filled urban areas. The danger of CO2 emissions had reached such a high level of concern that President Johnson gave a speech to Congress in 1965 warning of the dangers of greenhouse gas emissions, “This generation has altered the composition of the atmosphere on a global scale through ….a steady increase in carbon dioxide from the burning of fossil fuels… The longer we wait to act, the greater the dangers and the larger the problem.” It is important for younger readers to understand that our leadership has been very aware of what we have been doing to the planet’s ecosystem since the 1960’s. The question to ask is: why so little has been done to correct our course?

Important Messages of the Day

To get to an answer to that question, it is important to understand the larger context that gave rise to the first Earth Day, and what has subsequently transpired. Like many other nascent environmentalists, Rachel Carson’s “Silent Spring” was truly formative, for me, as a college freshman in 1964. Ms. Carson warned us about the environmental damage being done by the indiscriminate use of pesticides. Other seminal works that informed my generation’s viewpoint were works such as ecologist Garrett Hardin’s 1968 Essay, “Tragedy of the Commons,” which argued that when a number of people enjoy unfettered access to a finite, valuable resource such as a pasture, they will tend to overuse it, and may end up destroying its value altogether. Even if some users exercise voluntary restraint, other users will merely supplant them, the predictable result being a tragedy for all. Other key influences included Paul and Anne Ehrlich’s ‘Population Bomb,’ published in 1968, which predicted grave environmental and social stress from the inevitable population explosion after World War II.

By 1969, environmental issues had become top of mind for many. In 1969, Senator Gaylord Nelson of Wisconsin, one of the Senate’s leading environmental leaders, had just toured the Unocal oil spill devastation on the coast of Santa Barbara. On his trip up the coast to San Francisco he read an article about recent anti-war teach-ins held on college campuses. He realized that this approach could be a promising way to communicate public concern to elected officials in Washington D.C. He believed that: "If we could tap into the environmental concerns of the general public and infuse the student anti-war energy into the environmental cause, we could generate a demonstration that would force the issue onto the national political agenda.”

Earth Day Teach-In

On September 8, 1969, Senator Nelson announced the planned Environmental Teach-In for Spring 1970 and invited the entire nation to get involved in what morphed into the first ‘Earth Day.’ In response, I established a small student group in October 1969, to help coordinate the Earth-Day Teach-In for the Pacific Northwest states.

The national response to the April 22, 1970 Earth Day Teach-In was inspiring, and reverberated throughout the entire society. Illustrating society’s overwhelming support that day was NBC’s Today Show’s host, Hugh Downs, who opened their weeklong Earth Day-focused programming as follows:

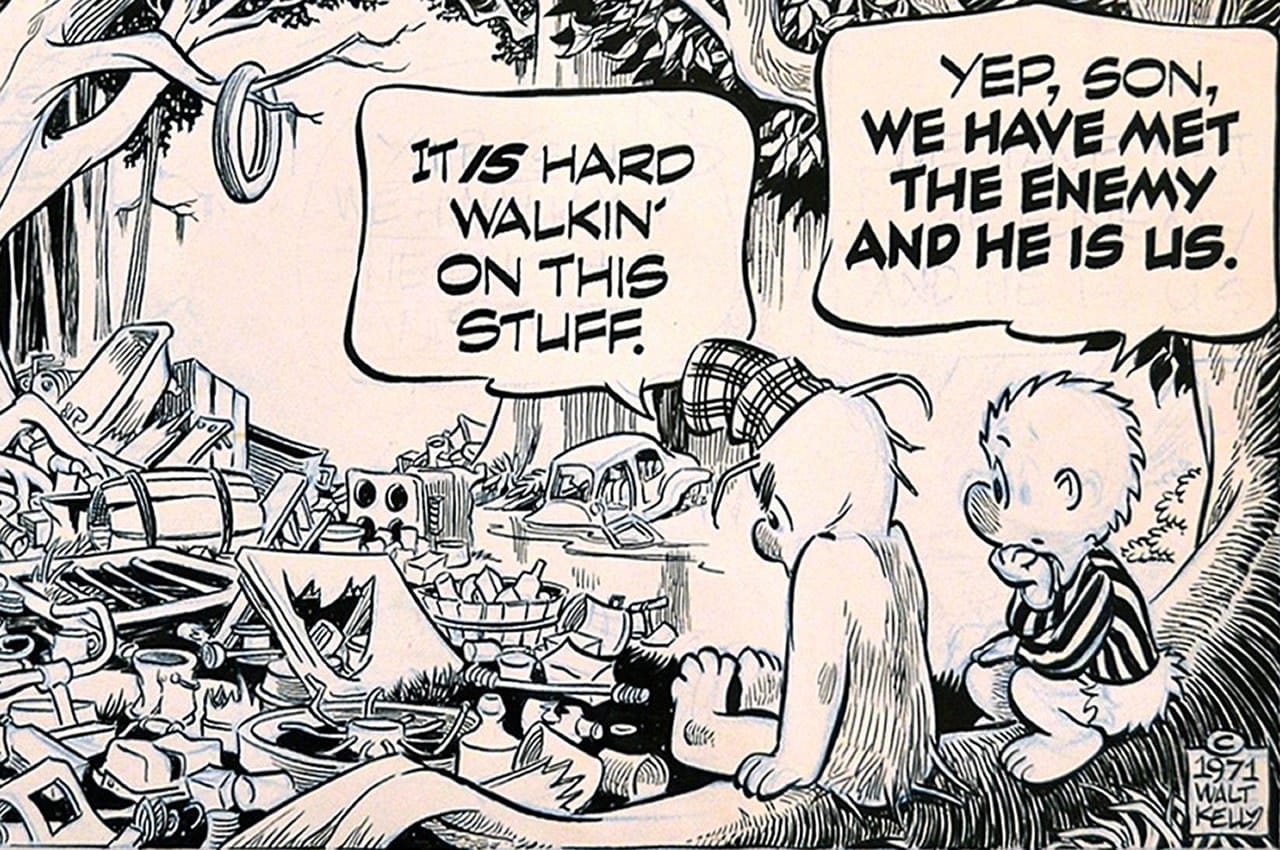

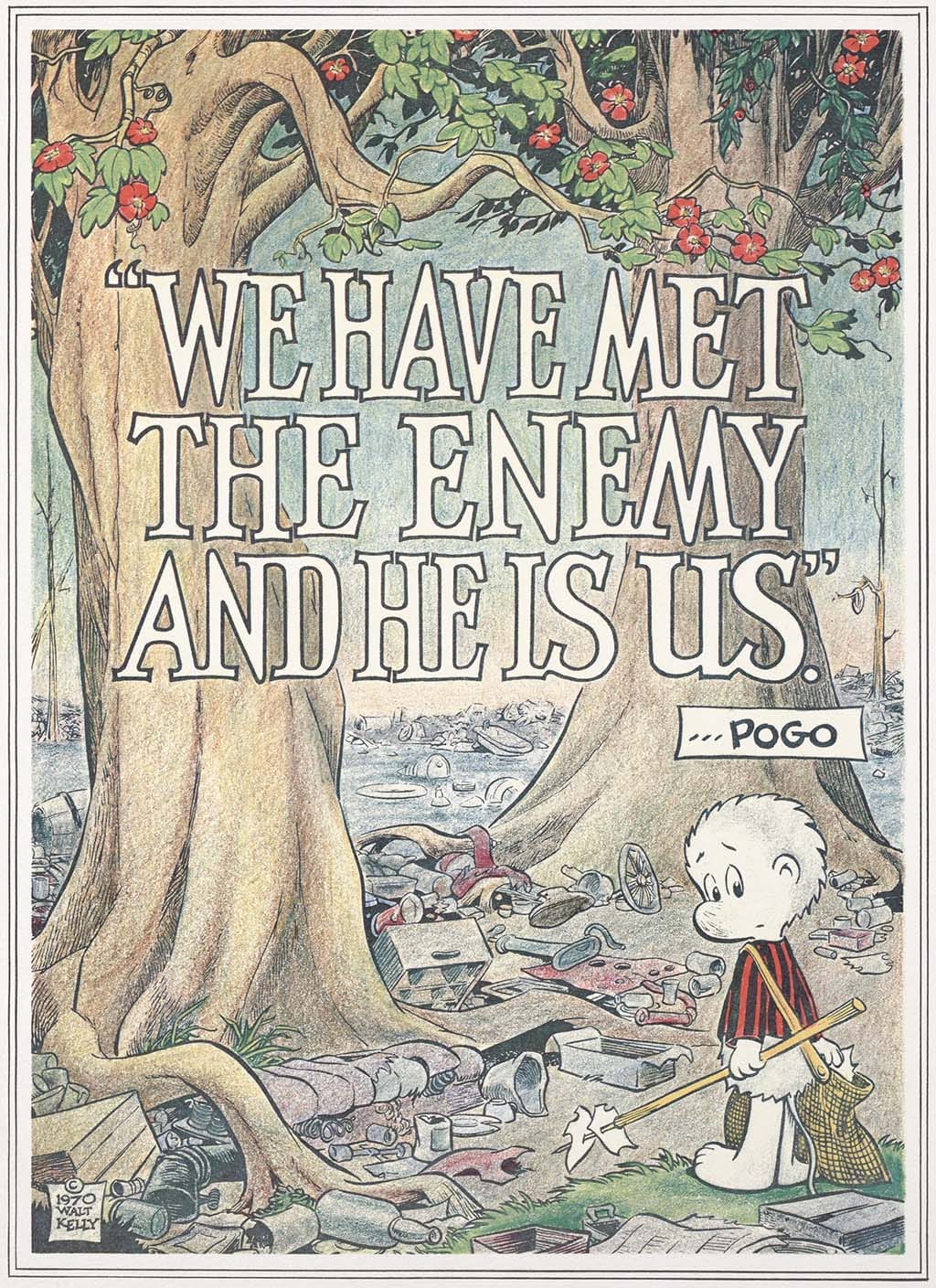

“Our Mother Earth is rotting with the residue of our good life. Our oceans are dying and our air is poisoned….do we go on demanding more and more…until we suffocate or die of plaque or famine?” This general attitude was unambiguously conveyed by Walt Kelly’s iconic Earth Day poster of Pogo saying, ‘we have met the enemy, and he is us.”

At this point, environmental concerns reached the highest offices in the U.S. with President Nixon's State of the Union Address, calling it, "The great question of the '70s." Nixon said, "Shall we surrender to our surroundings or shall we make our peace with nature and begin to make reparations for the damage we have done to our air, to our land and to our water?”

Persistent Environmental Issues

Much of what was set in motion that day has had positive and long-standing impacts, and certainly should not be diminished. But over these last 54 years, many of the fundamental issues that gave rise to the first Earth Day remain unaddressed. Failing to address those fundamentals has backed us into our current situation.

- Since 1954, humanity has wiped out over half of all mammals, birds, fish and reptiles. Some estimates suggest that humanity now consumes global resources at a rate requiring 1.8 earths to replace supply in time to meet the clean water, secure nutrient, affordable shelter and clean energy needs of our children and grandchildren.

- Year-after-year we continue to document increases in the atmospheric concentration of greenhouse gasses, while America has recovered the mantle of the world’s largest oil and gas producer, surpassing all of our past annual outputs, despite the current administration’s purported commitment to a ‘green’ agenda.

- In 1972 a team lead by MIT researchers examined the five basic factors that combine to limit material growth on this planet – population growth, agricultural production, nonrenewable resource depletion, industrial output, and pollution generation. Their report, ‘Limits to Growth’, determined that mankind can live indefinitely on earth if we impose limits on the production of material goods that are consistent with nature’s constraints, conclusions we have clearly failed to fully embrace.

- Returning to our opening question - why are we still failing? The reasons are many, of course, but all center on the strengths and weaknesses of human nature. Chief among them is hyper-consumerism. If you are so inclined, it’s worth revisiting Vance Packard’s two seminal books on the creation of the post-war consumer society which underpins much of the stress we have put on the environment. In ‘The Hidden Persuaders," the first published in 1957, Packard explores advertisers' use of consumer motivational research to manipulate expectations and stimulate desire for products, In his 1964 book ‘The Naked Society’, he analyzes advertisers' unregulated use of private information to drive marketing campaigns. Sixty years later we’re still dealing with these same issues, only increasingly enhanced through social media and the misguided goal of expanding American-styled consumerism throughout the world.

- Putting a statistical face on the historic rise of consumerism since 1970 can help put hyper-consumerism in perspective. Since Earth Day 1970, United States’ GDP per capita has increased 250% while global GDP has grown a momentous 500%. U.S. air travel has grown 500%; U.S. vehicle licenses increased 200%, with households with 2 or more cars increasing from 35% to 57%. Since that first Earth Day the number of vehicles on earth has skyrocketed from 250 million to nearly 1.5 billion, increasing 600%. Thanks to ‘fast fashion’ the average wardrobe in the U.S has increased over 100% since 1970. But at what price? With the clothing industry contributing over 5% of greenhouse gas emissions and dumping over 200,000 tons of synthetic microfibers into the marine environment every year, we’re paying a very high price for cheap clothing. Our homes in the U.S. provide another startling example of hyper consumerism. In 1950, the average home was just under 1,000 square feet (sq. ft.). During the postwar boom, it grew to 1,500 sq. ft. by 1970; but since the first Earth Day it has ballooned to nearly 2,700 sq. ft. today. These same growth trends are even more pronounced in the less developed—but catching up to the US—economies around the world.

- Meat production for global fast-food chains offers another example of the impact of unbridled growth. Converting land to grow crops to feed and to graze cattle are among the biggest drivers of deforestation in the Amazonian basin, with studies by Cornell University scientists calculating that the current rate of tropical deforestation, alone, could raise global temperatures nearly 2.0 Fahrenheit by 2070.

Root Causes: Hyper consumerism + Population growth

I can never forget the revolutionary zeal that fueled the First Earth Day, when students at San Jose State University bought and buried a new Ford in the center of the campus to protest the impact of cars on the environment in a ‘Survival Faire’ just before Earth Day. But that zeal has somehow been tempered and institutionalized. Now events focus on recycling and “reuse” programs that potentially touch on no more than the waste we generate unfortunately expropriating the original spirit and redirecting the intent of the first Earth Day.

While hyper-consumerism is an important contributor to our current environmental state, the significant environmental impact of the population explosion this last century cannot be ignored. Although there is much hand-wringing regarding the potential impact of falling populations in some quarters, these arguments hide uncomfortable truths about the ‘wrong’ people facing population decline, while the gross numbers tell a very different story regarding environmental impact. When my grandmother was born, there were 52 million people in America and 1.35 billion globally. That number had risen to 142 million in the U.S. when I was born and 2.3 billion worldwide. Today there are 330 million in the U.S., with global numbers having reached 8 billion and looking like they will reach 10 billion within 30 years or even sooner. By 2070, the U.S. population is estimated to grow to 475 million, nine times the population during my grandmother’s birth. Even assuming that new technology will enable us to cut our per capita environmental impact to half of the per capita impact of my grandmother’s generation--which is unlikely--the U.S. would still negatively impact the planet five times more than my grandmother’s generation. To say that population growth coupled with hyper-consumerism has not been one of the fundamental causes of our current environmental state belies these stunning, fact-based growth curves.

Obstacles to Progress

Layered on top of these fundamental drivers are three complimentary obstacles to achieving a sustainable future. The first is the prevailing global economic viewpoint, that continued economic growth, as measured by GDP, is an unquestionable requirement with long-term societal benefit. By definition, GDP growth is fueled by two necessary and intertwined ingredients – a growing population and increased consumption, giving rise to Wall Street’s knee-jerk fear of possible falling populations. The U.S. economy is a forceful testament to Vance Packard’s ‘Hidden Persuaders’ who have created a continually growing GDP fueled by 80% consumer spending. Unfortunately, continuing to measure our personal well-being divorced from sustaining the natural world will only lead to folly.

Simon Kuznets, who first recommended in 1937 that the US Treasury adopt GDP among the suite of metrics they should use to evaluate the impact of, and choose what policies and spending priorities to set, adamantly advised in the original report in which he advocated for GDP, that GDP not be seen as or used as an indicator of human welfare. His report goes on to state: “Economic welfare cannot be adequately measured unless the personal distribution of income is known. And no income measurement undertakes to estimate the reverse side of income, that is, the intensity and unpleasantness of effort going into the earning of income. The welfare of a nation can, therefore, scarcely be inferred from a measurement of national income as defined above.”

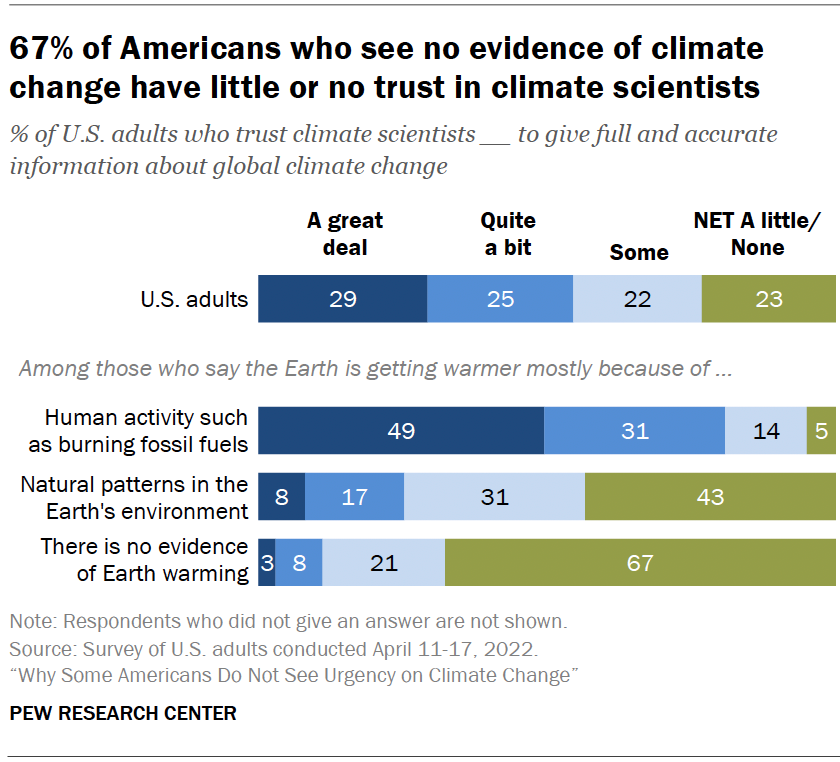

The second major obstacle to addressing environmental challenges in a democracy is the combined effects of peoples’ belief systems. The latest U.S. polls show that 40% of Americans do not believe that global warming is caused by human actions. And while just over half believe that science can lead to mostly positive effects on society, 45% of us do not believe in evolutionary science. With large blocks of American voters inclined to reject scientific findings, our various institutions will be severely tested to meet environmental challenges. Unlike the period that gave rise to the first Earth Day, when opposition to environmental policies was driven mainly by corporate self-interest, the 2024 Earth Day faces a political context in which both sides use environmentalism vs. capitalism as a wedge issue, making it almost impossible for society to chart a path to survival.

Finally, there is much euphemistic discussion regarding energy transformation, technological innovation and structural changes. I’m a full-throated believer in the continuing potential of scientific inquiry and sweeping innovation. However, we already have in-place a global physical infrastructure that supports—at least for now--8 billion people, embedded political systems designed only to maintain short-term social stability, and an economic model founded on competitive and limitless growth. Morphing these institutional values into a newer world view that recognizes natural restraints and the need for longer-term sustainability will be a tall order.

Guidance from the First Earth Day

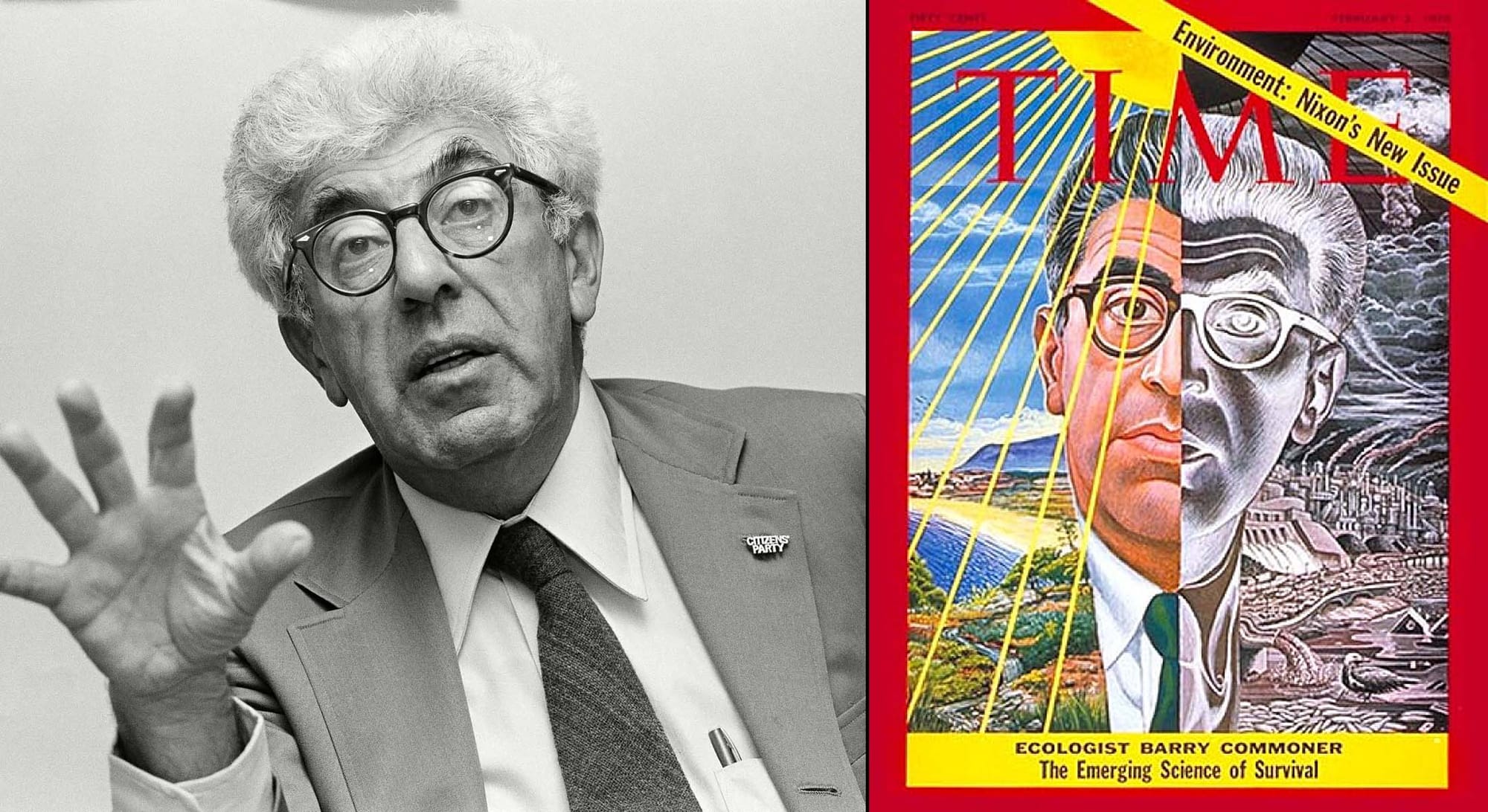

The first Earth Day did leave us with some guidance to chart a better path forward. More philosophy, perhaps, than anything else, but worth considering. The first important guidance came from Barry Commoner, an ecologist at Washington University in St. Louis, and leading light in the first Earth Day. His 1971 book, ‘The Closing Circle,’ argued that it is necessary to restructure economies to conform to the four laws of ecology:

- Everything is connected to everything else

- Everything must go somewhere

- Nature knows best

- There is no free lunch

Other voices, based on ecological principles, argued that economics grounded on limitless growth was unsustainable. An economy based on long-term compound interest must eventually fail due to physical and mathematical impossibility on a finite planet. (Every debt-driven society that came before us has failed. How do we avoid that same outcome?) Who knows what wonders await humanity over a distant future, but over the short-term – decades to a century – we do not have the knowledge or technical ability to free ourselves from these constraints. They must become guideposts that we acknowledge and work within, as we chart a new path to avert potential climatic and resource dependent tipping points.

The Path Forward

The Challenges for Earth Days going forward are to first understand that the built-in assumptions and inertia of our current systems are unsustainable. We cannot magically replace what we’ve built, but we can learn from our mistakes. We can individually become advocates for moving toward a sustainable future guided by ecological constraints. And we can set examples.

More to come in future editorials regarding economic strategies for realizing a sustainable and more equitable future.

Citations:

The American Presidency Project: Special Message to the Congress on Conservation and Restoration of Natural Beauty. | The American Presidency Project

Garrett Hardin Society: https://www.garretthardinsociety.org/articles_pdf/tragedy_of_the_commons.pdf

Pinguet: http://pinguet.free.fr/ehrlich68.pdf

U.S. Dept. of the Interior: https://www.cerc.usgs.gov/orda_docs/CaseDetails?ID=942

President Nixon Foundation: https://youtu.be/5LpspwT0ZwA?si=ZfTTu-R0mBPNaT4m

Nelson Earth Day: https://nelsonearthday.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/nelson-26-18-ed-denver-speech-notes.pdf

SJSU King Library Digital Collections: https://digitalcollections.sjsu.edu/islandora/object/islandora%3A275

Encyclopedia Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Barry-Commoner

ABC News Frank Reynolds An SOS For Survival, April 22, 1970